If you are a current speaker of English as the first language, being named “bimbo” or having your band or business entity named “bimbo” may be one of the most insulting things ever happening to you. It might also be the case even fifty years ago. However, for an Indonesian pop music group that has borne the name since 1967, the name has been a blessing and has become synonymous with their creative longevity and commercial success.

It all started with a nameless band of three brothers knee deep in their love of flamenco, Latin beat, and popular folk music. All three had been accomplished musicians at that point and just got out of a creativity dead end occurring a couple of years prior. They had been booked for their first performance as a musical trio by the nation’s then only national television channel, TVRI. The show’s producer, Hamid Gruno, knowing that the band would perform flamenco and Latin songs, suggested a Spanish sounding name: Trio Los Bimbos, perhaps in the spirit of legendary Latin trio Trio Los Panchos. Ironically, the word bimbo itself is originally Italian, but later found usage as an American English slang term, originally meaning brutish and unintelligent man or woman, although perhaps the bimbo in Hamid Gruno’s mind was more of a dashing young man that Jim Reeves portrayed in his hit “Bimbo” from the 1950s. Gruno insisted that the name sounded good and it stuck with the group, although over the years they gradually took off the “Los”, the plural “-s” suffix, and the “Trio” from their name to become the band that they would become known as.

The story of Bimbo started with the six out of seven children of the Dayat Hardjakusumah-Uken family. Dayat Hardjakusumah had been nationally renowned as a journalist during the Indonesian revolution and war for independence. On the side, he was also a teacher, writer, and illustrator. The eldest sibling of the family, Samsudin (Sam), born in 1942, exhibited his love for both music and visual arts from a very young age. Knowing that his siblings, particularly his two brothers and three sisters, also displayed the same interest in music, he began helping hone their skills. At a very early age, the three brothers in the family started taking singing lessons from local priest H.R. Pattirane, who recognized the brothers’ talent and the rich vocal harmonies that they could create together.

The vocal lessons continued with Sam and his immediate younger brother Darmawan (Acil), he jammed with high school friends and formed the Alulas in the late 1950s. His musical career had seemed to be on the right track. However, when faced with choices after high school, he chose to attend the art school at the Bandung Institute of Technology, hoping to become a professional painter. Around this time, his band transformed into Aneka Nada, with him as leader and vocals, still with Acil on vocals and rhythm guitar; other members included high school friend Jessy Wenas on lead guitar, singers Memet and Alfons, bassist Iwan, drummer Indradi, and eldest son of the Sukarno, then-president of Indonesia (1945-1967), Guntur Soekarnoputra on guitar. The band released an EP in 1964, followed by an album under Lokananta presumably in the same year.

Recognizing his younger siblings’ talent, Sam encouraged his three youngest sisters (Yani, Tina, and Iin) to form a vocal group called Yanti Bersaudara (known internationally as Yanti Sisters), with the name Yanti being an acronym of the three sisters’ names. Sam also guided the youngest son in the family, Jaka, to form Aneka Nada Junior. The members included Jaka’s middle school classmate Ridwan Armansyah (Iwan), bassist and songwriter who also penned some songs for Yanti Sisters’ career. Sam also wrote many of her sisters’ songs, along with Aneka Nada’s Jessy Wenas. Yanti Sisters’ first tasted fame when they sang “Abunawas” for a movie in 1966. They rose to popularity rather rapidly as a premium female vocal group.

On the other hand and around the same time, Aneka Nada experienced a crushing fate around the same time. They parted ways after differences in musical direction. This was likely caused by the then cultural and political situations. The Indonesian leadership under Soekarno cracked down on rock n’ roll music, fearing that the popular music would Westernize Indonesian youth. Popular national band Koes Bersaudara were arrested for performing The Beatles’s songs. Not long after, a political coup blamed on the Communist Party of Indonesia erupted, followed by a communist purge and genocide instigated by certain departments within the Indonesian army. Sukarno was deposed and Indonesia ushered in a new era, simply referred to as Orde Baru (the New Order).

During and soon after the turmoil, Sam and his brothers decided to take a break from music. Sam resumed his study and further honed his painting skills, while his brothers also started attending college. Yanti Sisters looked for a more stable market for their music and found Singapore to be one. In 1967 they started recording EPs for Philips in Singapore, one of which, Sinbad, would be expanded as a full-length album under Remaco. They switched labels to Polydor, with their first release being a Christmas album in 1968. Part of the royalty payment from the album went into ordering three custom acoustic guitars. The sisters gifted the acoustic guitars to their three brothers, still in musical hiatus at that time. The guitars were meant to encourage them to consider practicing and performing again. They did practice, this time focusing on their love of Latin music, particularly in the format of trio romantico and their three-part harmony and were often guided by H.R. Pattirane, the person who taught them how to sing. The constant practicing and strengthening of their vocal harmony led them to their first TV performance. The rest, they say, is history. But a very long history it is.

Like Yanti Sisters (and also numerous Indonesian musical groups of the late 1960s), the trio turned to Singapore for a more accepting and stable market. This decision was also partly fueled by the rejection from Remaco, then Yanti Sisters’ Indonesian label, that did not believe that there was a market for Latin-influenced music in Indonesia. After fulfilling their residency contract in Ming Court Hotel in late 1970, they secured a one-album contract with Fontana/Polydor. With the help of legendary backing band Maryono and His Boys, who were also in Singapore for a stint, they put together an album consisting of Indonesian songs on one side and songs in English on the other side.

The songs in English were likely part of their repertoire in Ming Court Hotel, which include songs such as “El Condor Pasa”, Simon and Garfunkel’s “Cecilia”, and “Light My Fire” (in a Latin style, akin to Jose Feliciano’s version). The Indonesian songs were all written by outside writers. Some of which were covers, while two of the songs, “Melati dari Jayagiri” (“Jasmine from Jayagiri”) and “Flamboyan” (“Flamboyant Blossom”), were written by Jaka’s middle school classmate Ridwan Anwarsyah, now known by his pseudonym Iwan Abdulrachman. These songs became two of Bimbo’s most lasting hits and was the start of a long collaboration with Iwan. From this album on, the trio started calling themselves Trio Bimbo, dropping the “los” and the “-s” suffix. This was in keeping with their intent on presenting themselves as an Indonesian group.

Despite being a limited release, the album was met with success and was pretty much sought after, both in Singapore and Indonesia. Seeing that there was indeed a market for the Latin-influenced/folk music that the trio offered, Remaco changed their mind and offered the trio a recording contract. Their first effort was an almost squarely folk album consisting of original songs composed by Sam and Jaka. The album showcased the two brothers’ knack for delicate yet memorable melodies, poetic lyrics, and for writing ballads influenced by a variety of European folk music and their own Sundanese traditional music background. Their youngest sister Iin also featured in several songs as both lead and background vocalist. Iin’s involvement occurred not only because the trio needed the necessary high register vocals, but also because Yanti Sisters had recently disbanded. After getting married, Yani and Tina decided to focus on building their families, leaving Iin as the only singing Yanti Sister.

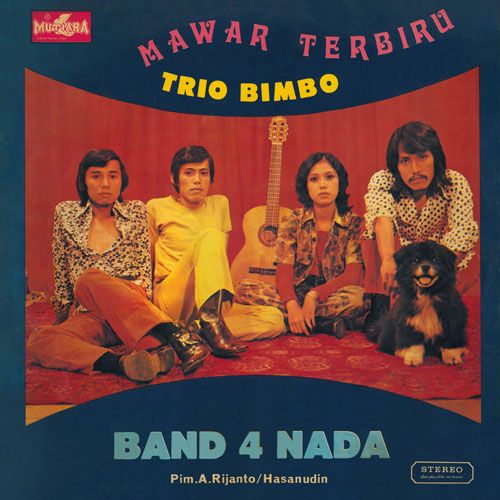

While their first Remaco album was rather well received, it was deemed necessary for the group to update their sound, to create a fuller band experience whilst retaining some of their original sound from their debut. To accomplish this, Remaco paired Bimbo with 4 Nada, the label’s most prolific and well-known session band, then led by accomplished producer, songwriter, and keyboardist A. Riyanto. The first few sessions with 4 Nada resulted in two albums, one released with Remaco and the other released under Remaco’s imprint, Mutiara. 4 Nada’s studio proficiency gave Bimbo a cleaner yet more complex sound, while still allowing room for the siblings’ creativity, harmony, and musical influence to shine through. For instance, the first song in the Remaco album, “Abangku Sayang Dibawa Orang” showed clear influence of mariachi music, which the brothers often adapted for their Singapore stint. Their harmonies filled the entire album and soon became an indispensable part of their landmark sound.

For the Mutiara album, which was called Mawar Terbiru (The Bluest Rose) after one of the songs in the album written by Iwan Abdulrachman, Bimbo and 4 Nada ventured further into including elements of psychedelic pop, often represented in Sam’s arrangements and A. Riyanto’s organ playing. A. Riyanto’s treatment of Bimbo’s ballads also gave them symphonic quality, such as in Iwan Abdulrachman’s “Angin November”, which became one of the most well-known songs from the Mutiara album. The Mutiara album contain many of Bimbo’s landmark characteristics that people would later associate with their music. Chief among these are the three- and four-part harmonies (with Iin), the poetic lyrical tendency, the folkish-and-symphonic ballads, and the putting forth of each sibling’s unique vocal style.

At this point in their career, it was clear that while they sang great in harmony, each member started filling their own role in the group. Sam’s tenor is perhaps the most recognizable with clear influence of Sundanese vocal music in his voice. He is often the voice of Bimbo’s two musical extremes: upbeat, and sometimes psychedelic, numbers and contemplative minimalistic ballads. When Bimbo started writing pop songs in Sundanese, Sam’s voice is the logical choice for the songs. Acil’s rich vibrating baritone is suitable for more dramatic and symphonic ballads. While he did not sing too many leads, he sang on some of the most famous Bimbo ballads. Acil’s voice is unique among his brothers and among other Indonesian pop singers in that it superficially sounds like the male golden voice popular in the 1960s, but it actually represents a complex classical influence of church choir singing and Indonesian seriosa singing, a genre influenced by German lied music.

Jaka, while trained in soprano singing, very rarely sang lead even though he is present in almost every Bimbo harmony. As Bimbo became deeply embroiled in recording industry, Jaka became more interested in the production side of their music. As the most accomplished guitarist in the family, Jaka handled most of the guitar work, which he shared with Sam for rhythm guitar and the home band guitarist (in 4 Nada’s case, Eddy Syam), if available, for lead guitar. Jaka’s guitar playing, in particular his acoustic melodies and arpeggios, grew to become Bimbo’s most recognizable sound apart from their voices. While it started out as an addition at first, Iin’s voice turned out to be indispensable for the group’s sound. In the absence of a male soprano, Iin’s high soprano and unique phrasing and pronunciation provides a much needed fullness to the group’s sound. Iin’s integral role further prompted the group to be credited as Trio Bimbo + Iin during their early Remaco days.

Starting from their Remaco debut, Jaka and Sam had been the main writing team for Bimbo, with Acil sometimes chipping in. The songwriter(s) usually already had an idea of whose voice would be suitable for a song they wrote. Hence, although Sam often sang most of the songs he wrote, sometimes he had Acil or Iin’s voice in mind when he was writing a particular song. The same thing also applied to Jaka’s songs.

Apart from the songs written from within the group, they also sourced out songs written by outside composers. This has become somewhat of a Bimbo trademark as well ever since their Singapore album, which further continued during their Remaco years. Remaco songwriters A. Riyanto and his cousin Is Haryanto, as well as well-known composers such as Titiek Puspa, also contributed songs to Bimbo’s released. However, Bimbo also sometimes turned to certain composers or lyricists outside of the group and their label. While bands and singers under Remaco contract often relied on other composers, hiring composers not on Remaco’s payroll was very rare; Bimbo became somewhat of a pioneer in this type collaboration in the Indonesian pop music industry.

One of the most famous songwriters for Bimbo whose name even became synonymous with Bimbo’s early success was none other than Iwan Abdulrachman, whose long history with Bimbo started with several songs he composed for Yanti Sisters, and later, three songs for Bimbo’s debut album. His penchant for both contemplative and dramatic ballads meshed well with Bimbo’s sound, so much so that much of Bimbo’s commercial success in the first half of the 1970s was often credited to the group’s interpretations of his songs.

However, there is one other songwriter who was as prolific and as influential to Bimbo as Iwan: Koeswandi. Often credited as Wandi or his stage name One Dee, he had been, like Iwan, Bimbo’s members’ old friend although his past connections with the group have not been as very well documented. Like Iwan, Wandi also wrote some of the most well-known Bimbo ballads, such as “Serani di Noda”, although he was also a little bit more adventurous when it comes to songwriting, giving Bimbo sound the sprinkles of psychedelic pop from time to time. This is hardly surprising, however, as outside Bimbo, Wandi was known as an innovator of Sundanese pop music through his introduction of psychedelic and hard rock elements into the genre.

Bimbo even went one step further in terms of their collaboration with songwriters and lyricists. They reached out to the poetic community and collaborated with a number of Indonesia’s most prominent poets. While their Remaco debut had already featured two songs whose lyrics were written by famed poet Taufiq Ismail, their third and final album with 4 Nada saw them work with other prominent poets, Wing Kardjo and Ramadhan KH. The album, called The Best of ’73, was perhaps Bimbo’s most poetic and literary, which further increased their critical reputation as the rare popular music group that was highly regarded within literature circles.

After the fruitful 3-album spell with 4 Nada, Bimbo were finally on their own. This was likely caused by the drama 4 Nada stirred with Remaco, particularly with A. Riyanto wanting to have his own pop band, which resulted in the formation of The Favourite’s Group (read my previous post on The Favourite’s Group here). In the absence of 4 Nada, Bimbo saw the importance of forming a solid recording and touring band that could function solidly as a unit, working as one mind in the studio and on stage.

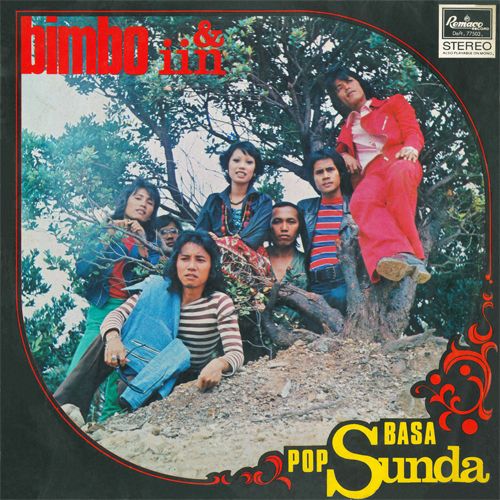

Although the group would still center on the siblings, other members were recruited to form what would become Bimbo’s band. It was around this time, the group finally dropped the “Trio” from their name, and began recording and touring as Bimbo & Iin, a seven-piece band. The band comprised the four siblings and three members of the rhythm section. On bass was a name already mentioned quite often above, Iwan Abdulrachman. While he had already shown himself as a talented songwriter, Iwan proved in Bimbo that he was also a skillful bassist, supplying the group with rich, often-pounding basslines. On drums was Rudy Suparma; while not much is known about him, he was both Bimbo and Wandi’s old associate. On piano and various keyboard instruments was Indra Riva’i, formerly of the experimental progressive rock Harry Roesli Gang. His experience with playing and composing complicated progressive rock music was translated into Bimbo’s lush musical layers and textures through his mastery of various keyboard instruments and synthesizers, which only a handful of Indonesian bands owned back in the day. Indra’s prominent role in the group and knowledge of diverse musical styles and instruments led him to be trusted to handle the general arrangements for some of the band’s most successful Remaco albums.

As a seven-piece band, Bimbo reached their most prolific recording period. While their fellow Remaco labelmates were often forced to be prolific, reflected in the production of subpar albums, Bimbo differed in seemingly always having a clear concept and roadmap for each of their projects. Apart from their collaborative approach with poets and other composers mentioned above, their main pop albums maintained and expanded upon the sound that they had achieved with 4 Nada. Among other Remaco artists, Bimbo was also unique in that they were one of the very few bands who did not simply title their albums Vol. 1, Vol. 2, and so on. Each album seemed to be curated and produced to follow a certain concept or to more or less form a certain idea, albeit sometimes not very faithfully.

Like many artists under Remaco, Bimbo became very prolific. This productivity was not theirs alone as other artists under Remaco were also considerably prolific, some were even forced to be so. Remaco was notorious for paying a flat fee without royalty to their artists. This was a system not uniquely theirs in the Indonesian commercial music industry but was strongly enforced by them and their imprint labels. The only way that an artist could make more money or get more advance payment with Remaco was to record more albums, sometimes even without regards to quality. Worse still, Remaco often insisted that their artists tailor their albums to cater to a more general market taste or to follow a certain trend in music, even though that trend is so far removed from an artist’s personal style. A notorious example of this came about when they made AKA, a rock band under their label, record an album of qasidah songs, Islamic songs in a style that starkly contrasted AKA’s hard rock brand that they had honed for much of the early 1970s.

Few bands under Remaco were able to keep up with this method. Koes Plus is another shining example for other bands under Remaco, as they kept things simple and interpreted musical influences and trends only as much as the band could handle, making them simple and unmistakably Koes Plus at the same time. On the other hand, Bimbo tried a more collaborative method to keep things fresh and exciting, although this meant diminishing returns for the group as they had to pay other artists outside of the group.

During their later Remaco years, many of Bimbo’s “side albums”, meaning the albums outside their mainstream pop releases, were produced in collaboration with outside involvements. Often certain bands had to dip into a certain genre very different from their mainstream musical output, or a genre they had no experience in, like AKA mentioned above. Bimbo, on the other hand, often chose to collaborate with other artists and composers from outside the band and outside Remaco, just like what they did with the poets in their previous albums.

A great example of this collaboration is Bimbo’s series of Sundanese pop albums. At the height of the popularity of pop songs in Indonesian ethnic languages, Bimbo dug their Sundanese roots while realizing that they have been so influenced by other varieties of local and international musical styles. To better connect with their roots and present the authenticity of their mother culture, they invited legendary Sundanese comedian Ibing to pen the lyrics to their Sundanese songs. While not a professional musician, Ibing was a prominent comedian and comedic scriptwriter in Sundanese and was highly familiar with Sundanese wordplays, figures of speech, and traditional Sundanese music in general. Traditionally, Sundanese pop songs were also widely known for their humorous content, making Ibing’s experience even more useful, as he was able to string jokes after jokes and wordplays after wordplays in the melodic spaces that Bimbo provided for him.

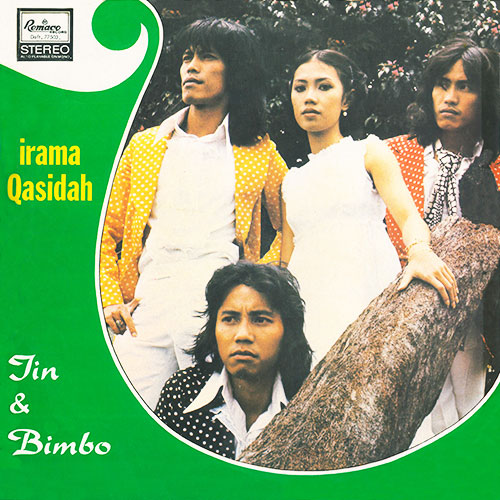

Another series of Bimbo’s “side albums” that were met with considerable success was their collection of religious, Islamic songs. The demand for such religious songs came about in the second half of the 1970s, mainly in a genre called qasidah introduced by the group Nasida Ria. Originally a poetic style in Arabic, qasidah in Indonesia transformed into a genre of popular Islamic music, often performed by a group of harmonizing singers. Nasida Ria represents the archetypal Indonesian qasidah style, which can be best described as heavily influenced by the diverse musical styles of the Middle East and Arab world with Indonesian lyrics of Islamic concepts of piety and morality.

While Bimbo also jumped on the bandwagon of this trend, they are often credited as a pioneer in seamlessly combining qasidah and pop music idioms, making the music more accessible to the general public. They had previously written more universally religious songs, such as “Tuhan” (“God”), which later became Bimbo’s lasting religious hit, and many of Iwan’s songs, such as “Doa” (“Prayer”), concern spiritual experiences. However, although the members of Bimbo were all practicing Muslims, they were unsure about how they would approach the lyric writing, as qasidah music often requires deep understanding of Islamic concepts, histories, and verses from the Holy Quran. Fortunately for them, Taufiq Ismail, a poet who had written lyrics for the group several years prior, was rediscovering himself as a poet of Islamic verses through increasing piety and ongoing study of Islam. He wrote most of the lyrics for Bimbo’s first and second qasidah albums, the start of an even longer collaboration which lasted well into the 2000s. For their subsequent qasidah albums, Bimbo enlisted lyrical assistance from other Indonesian Islamic poets as well.

The qasidah albums proved to be a great success for Bimbo, further proving their versatility and well-honed craft, as well as collaborative approach. About a decade later they would revisit their original qasidah songs and write new ones as well, giving them further and longer lasting success, which will be explored in the second part of this post.

In their mainstream pop department, Bimbo’s richest pop music production arguably reached its peak with the Indonesia album series (1976-1977), which consist of three volumes of Indonesia Antik and one Indonesia Baru album. These albums show how rich Bimbo’s musical inspirations and influences were, and how the group managed to produce their distinct sound amidst all these influences. In short, the Indonesia albums can be defined as albums that summarize the musical influences that inspired Bimbo in their career. These are represented by songs in various styles by composers from the previous decades, or songs composed from within group (including Wandi and Iwan) that emulated certain musical styles. These range from classically influenced national songs, regional traditional music (gambang, Malay, keroncong), and global styles that were prominent in the group’s early career, such trio romanticos, flamenco, mariachi, and country Western. They also paid tribute to their contemporaries and immediate predecessors, such as Iskandar, Mochtar Embut, Titiek Puspa, and A. Riyanto by recording their songs. The composers within the band, particularly Sam and Wandi, also attempted to emulate specific musical styles. Wandi’s “Berdiri di Atas Jembatan Semanggi (“Standing at Semanggi Bridge”)”, for instance, is chock full of influence from the rock band Queen, particularly in its vocal arrangements.

Towards their ten years of existence and six years of recording career, Bimbo had become a considerable musical force known not only for their lush and well harmonized ballads. Due to the many collaborations with many artists and experiments with a wide variety of genres, Bimbo also became known for their humorous, light-hearted, upbeat songs. Many of these songs are based off of Indonesian wordplays or short sketches. The most famous among these are arguably the “body parts” quadrilogy: “Mata” (“Eye”), “Tangan” (“Hand”), “Bibir” (“Lips”), and “Kumis” (“Moustache”), in which the group explored the rich possibilities of wordplay in Indonesian.

Many of Bimbo’s later comedic songs cross over to the realm of social critique as comedy is often considered the ripe genre for a such a purpose. Some of them are subtle and rely on comedic effect, such as “Singkatan” (“Abbreviations”), a song consisting of made up abbreviations which jabs at Indonesian people’s (and government institutions’) fondness of creating confusing abbreviations and acronyms. Some are more frank and unashamedly satirical, such as “Tante Sun” (“Aunty Sun”). The critique of nepotism in the song runs deep, as the titular character, a rich and busy career woman, is seen as a parody of the wives and daughters of government officials who were often handed political positions and businesses despite having no qualifications. The ruling Indonesian New Order regime was not happy with the song and issued a cease-and-desist order for the performance of the song. This, however, did nothing to stop Bimbo from writing more critiques in their later albums.

Bimbo celebrated their 10th anniversary by releasing an album called Perjalanan (Journey). While they were thankful for their longevity and success, things were about to go downhill from there, at least for a while. Remaco was going bankrupt, likely due to mismanagement and greed. After recording a couple more albums, Bimbo was let go in 1978. With Remaco’s bankruptcy, the rest of their contract was transferred over to Purnama. Bimbo immediately recorded Tahun 2000 (Year 2000) with Purnama but opted out of a longer contract and decided to look for another record label instead. With the pop music scene changing drastically by the end of 1970s, finding a suitable label and rediscovering themselves were proven to be quite a challenge which they tackled in a variety of ways in the second part of this post.

One reply on “Bimbo: An Evolution of Pop Music Success Story (1)”

[…] saat saya tengah menulis sejarah Bimbo dalam bahasa Inggris (bagian pertama bisa dibaca di sini), saya terkenang sebuah album Bimbo yang sering saya sengaja putar sewaktu saya masih punya Sony […]

LikeLiked by 1 person